GNOME Human Interface Guidelines 2.2.1

The GNOME Usability Project

Copyright © 2002-2010 Calum Benson, Adam Elman, Seth Nickell, colin z robertson

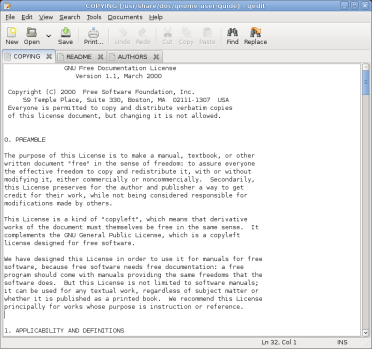

Permission is granted to copy, distribute and/or modify this

document under the terms of the GNU Free Documentation

License, Version 1.1 or any later version published

by the Free Software Foundation with no Invariant Sections, no

Front-Cover Texts, and no Back-Cover Texts. You may obtain a copy

of the GNU Free Documentation License from

the Free Software Foundation by visiting their Web site or by writing to:

Free Software Foundation, Inc., 59 Temple Place - Suite 330,

Boston, MA 02111-1307, USA.

Many of the names used by companies to distinguish their products and

services are claimed as trademarks. Where those names appear in any

GNOME documentation, and those trademarks are made aware to the members

of the GNOME Documentation Project, the names have been printed in caps

or initial caps.

Abstract

This document tells you how to create applications that look right, behave

properly, and fit into the GNOME user interface as a whole. It is written for

interface designers, graphic artists and software developers who will be creating

software for the GNOME environment. Both specific advice on making effective use

of interface elements, and the philosophy and general design principles behind

the GNOME interface are covered.

This document tells you how to create applications that look right,

behave properly, and fit into the GNOME user interface as a whole. It

is written for interface designers, graphic artists and software

developers who will be creating software for the GNOME environment.

Both specific advice on making effective use of interface elements,

and the philosophy and general design principles behind the GNOME

interface are covered.

These guidelines are meant to help you design and write applications

that are

easy to use and consistent with the GNOME desktop. Following these

guidelines will have many benefits:

Users will learn to use your

program faster, because interface elements will look and

behave the way they are used to.

Novice and advanced users alike will be able

accomplish tasks quickly and easily, because the interface

won't be confusing or make things difficult.

Your application will have an attractive look

that fits in with the rest of the desktop.

Your application will continue to look

good when users change desktop themes, fonts and

colors.

Your application will be accessible to all

users, including those with disabilities or special

needs.

To help you achieve these goals, these guidelines will cover basic

interface elements, how to use them and put them together effectively,

and how to make your application integrate well with the desktop.

The recommendations here build on design aspects that have

worked well in other systems, including Mac OS, Windows, Java

and KDE. At the same time they retain a uniquely GNOME flavor.

![[Tip]](images/tip.png) | Remember... |

|---|

|

Following the guidelines will make your job easier,

not harder!

|

Chapter 1. Usability Principles

This section explains some of the basic principles behind the more specific technical guidelines recommended in this document. We believe that these principles are important for all application development.

Remember that the purpose of any software application is to enable some group of people to accomplish a specific set of tasks. So, the first things to establish when designing your application are:

who your users are

what you want to enable them to do

For example, you may be designing an application that will enable engineers (software, electrical, or mechanical) to create diagrams. You may be designing an application that will enable system administrators to configure and monitor a web server. You may be designing an application that will help elementary school students to learn math.

The important thing is that you know your audience, and you understand both their goals and the tasks necessary to achieve those goals. There are a large number of professional interaction designers who write books and teach courses on design methods that can help with this process, many of which are extremely useful— see the Bibliography for a selection. Most of these methods, however, boil down to specific ways of understanding your users, understanding the tasks you want to help them accomplish, and finding ways to support those tasks in your application.

1.2. Don't Limit Your User Base

If you are designing an application for use by engineers, or by children, or by system administrators, be sure to create an application that can be used by all engineers, children, or system administrators, including those with disabilities or those who are native speakers of a language different from yours. Be aware of accessibility issues and internationalization and localization issues, many of which are addressed by the guidelines in this document.

Accessibility (sometimes called a11y) means enabling people with disabilities of some kind to participate in life's activities: in this case, specifically to use your software. For example:

Color-blind users may not be able to use your application if you rely only on color-coding to distinguish different types of information

Users with hearing impairments may not be able to use your application if you rely on sounds to indicate critical information

Users with limited movement may not be able to use your application if you don't provide keyboard equivalents for commands

Your software should also be usable with voice interfaces, screen readers such as Gnopernicus, alternate input devices, and other assistive technologies. The standard GNOME libraries do most of this work for you, but with a little extra effort you can make your application every bit as useful to users who rely on those technologies as to those who don't.

GNOME has excellent inbuilt support for accessibility by means of the ATK and GAIL libraries, which in many cases can do most of the work for you. More information on accessibility in GNOME can be found at the GNOME Accessibility Project.

1.2.2. Internationalization and Localization

Internationalization means designing software so that it can function in different language environments. Localization is the process of actually translating the messages, labels, and other interface elements of an application into another language.

GNOME has excellent support for both internationalization (also referred to as i18n) and localization (also referred to as l10n). In most cases, simply using standard GNOME APIs for displaying text and messages will allow you or others to localize your application for other locales. For more information on how to make your application localizable, see the Pango project home page (Pango is the GNOME library for rendering internationalized text), the GNOME Translations page, and the GNOME Translation Project page.

Sensitivity to cultural and political issues is also an important consideration. Designing icons and sounds, and even choosing colors requires some understanding of the connotations they might have to a user from a different part of the world.

Examples of elements it is best to avoid for these reasons include:

Pictures of flags or money

Maps showing political boundaries or contentious location names

Lists of countries or cities in non-alphabetical order (unless specifically requested or required by the context)

Icons depicting animals

Icons depicting only hands or feet

1.3. Create a Match Between Your Application and the Real World

Always use words, phrases, and concepts that are familiar to the user rather than terms from the underlying system. Use terms that relate to the user's knowledge of the tasks your application supports. For example, in medicine, the paper folder that contains all information about a specific patient is called a "chart." Hence, a medical application might refer to a patient record that contains the same information as a paper chart as a "patient chart" rather than as a "patient database record."

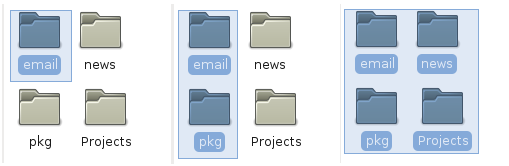

You can often take advantage of your users' knowledge of the real world by using metaphor— that is, a familiar concept from the outside world— to represent elements within your application. For example:

When using metaphors, however, it is important to neither take the metaphor too literally, nor to extend the metaphor beyond its reasonable use. For example, the capacity of a file folder should not be limited to the capacity of a physical file folder, which presumably could contain only a few documents before becoming unwieldy. On the other hand, a waste basket should not be used for anything other than holding discarded files. It should not be used, for example, to eject a removable disk such as a floppy or CD.

1.4. Make Your Application Consistent

Make your application consistent with itself and with other applications, in both its appearance and its behavior. This is one of the most important design principles, and probably the most famous, but it is also frequently ignored. While this document serves as the basis for consistency between GNOME applications, you are encouraged to look at and follow other application's conventions where this document provides no guidelines.

Consistency enables users to apply their existing knowledge of their computing environment and other applications to understanding a new application. This not only allows users to become familiar with new applications more quickly, but also helps create a sense of comfort and trust in the overall environment. Most of the recommendations in the GNOME HI Guidelines are designed to help you create applications that are consistent with the GNOME environment and other GNOME applications.

A word of caution: a mis-applied or incomplete consistency is often worse than inconsistency. If your application includes an menu item for consistency, but it is always disabled because your application does not actually support Undo, this will reduce the user's trust in the availability of Undo in other applications on their desktop. Either make your application support Undo, or eliminate the menu item.

1.5. Keep the User Informed

Always let the user know what is happening in your application by using appropriate feedback at an appropriate time. The user should never have to guess about the status of the system or of your application. When the user performs an action, provide feedback to indicate that the system has received the input and is operating on it. Feedback can be visual, audio, or both. If the system will take a long time to process the request, provide as much feedback as possible about how lengthy the operation will be. Types of helpful feedback include but are not limited to: cursor changes, animated "throbbers", progress indicators, audio feedback such as a beep, and error messages. Error messages should use simple language, clearly state the problem, and provide solutions or tell the user how to get out of the current situation if possible.

It is critical that feedback be accurate and precise. If you display a determinate progress indicator to display the state of completion of a task and it is inaccurate, the user will lose faith in progress indicators, and they will find the environment less usable. If you display a generic error message that indicates that there is a problem but fails to provide enough information to diagnose or solve the problem, your users will be unable to continue with their task.

See Chapter 7, Feedback and Section 3.4, “Alerts” for more information on feedback.

1.6. Keep It Simple and Pretty

Your application should enable the user to concentrate on the task at hand. So, design your application to show only useful and relevant information and interface elements. Every extra piece of information or interface control competes with the truly relevant bits of information and distracts the user from important information. Hence, don't clutter your interface, and don't overload the user with buttons, menu options, icons, or irrelevant information. Instead, use progressive disclosure and other techniques to limit what the user sees at any given moment.

Finally, present your information and interface elements in an aesthetically pleasing manner. A disorganized, cluttered-looking interface with a few elements can be just as distracting as an organized interface with too much information. Make sure that dialog elements are cleanly-aligned, and do not overuse or misuse color or graphics. If you know a graphic designer, seek their advice if possible— the guidelines in this document will help you with the basics, but there is no substitute for a trained eye.

See Chapter 8, Visual Design and Chapter 9, Icons for more information on designing the visual appearance of your application.

1.7. Put the User in Control

Remember that computers exist to serve humans. A user should always feel in control, able to do what they want when they want. This means you should generally avoid modes; users should be able to switch between different tasks (and specifically, different windows) at any time. See Section 3.1.3, “Modality” for more information on modes.

The user should also be able to tailor aspects of their environment to fit personal preferences. It is very important, however, to avoid the trap of allowing too much configuration, or allowing the configuration of parameters that most users will not understand or find useful to modify. Wherever possible, inherit visual and behavioral parameters from global preferences and settings such as the current GTK+ theme.

We all make mistakes. Whether we're exploring and learning how to use the system, or we're experts who just hit the wrong key, we are only human. Your application should therefore allow users to quickly undo the results of their actions.

If an action is very dangerous, and there is no way to undo the result, warn the user and ask for confirmation. Only do this in extreme cases, though; if frequently faced with such confirmation messages, users begin to ignore them, making them worse than useless.

In all cases, the user's work is sacrosanct. Nothing your application does should lose or destroy user's work without explicit user action. Among other techniques, this can be achieved by auto-saving backups of documents, and allowing multiple levels of undo.

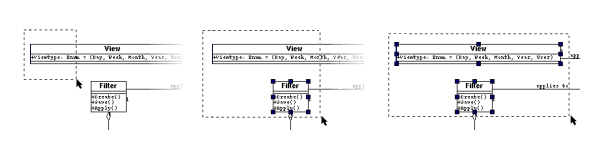

1.9. Provide Direct Manipulation

Wherever possible, allow users to act on objects and data directly, rather than through dialogs or explicit commands. For example, it is more intuitive to drag a circle object around in a diagram rather than selecting a "Move" command from a menu while the circle is selected. Simlarly, in an email application, allow the user to attach files by dragging them from the file manager and dropping them onto the message composition window if they wish.

See Chapter 10, User Input for more information on direct manipulation.

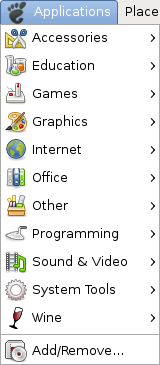

Chapter 2. Desktop Integration

There are two elements to basic integration with the user environment of the GNOME Desktop.

Place an entry for your application in the menu. This is the primary mechanism by which users discover and run applications.

If your application can open and save files, place entries for those file types in the application database and the document type (MIME) database. This allows the file manager and other applications to automatically launch your application when they encounter files your application can handle.

Do not add launchers or other icons to the desktop when your application is installed. The desktop is the user's space, and is reserved for icons that they explicitly request or add themselves.

GConf keys are required to have long and short descriptions for each key. Many keys have no interface through the application, so for someone administering the key values from another application each description field will be the only interface available to them.

Guidelines

Short Descriptions should be short, less than 8 words, describing the purpose of the key

Long Description should be complete in describing the possible values of the key and the effects that those values have on the application

Example 2.8. Example descriptions for GConf Keys from gnome-terminal

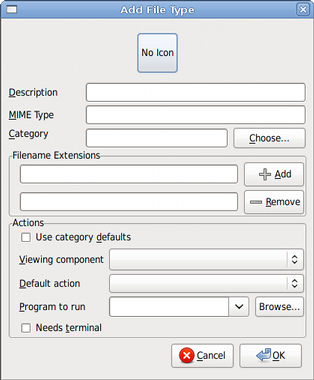

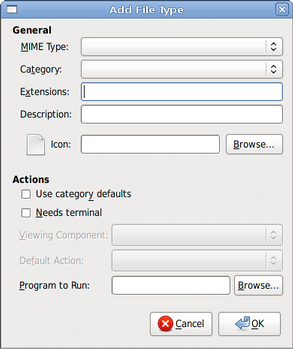

2.3. Mapping Document Types to Applications

The document type (MIME) database allows users to specify their preferred applications for opening different types of document. This is the mechanism by which Nautilus, Evolution and other applications decide which application to run when they encounter a document they cannot open themselves.

It is important for users to be able to double-click on documents they see on the desktop, such as files and email messages, and have them launch in their favorite application. Therefore, your GNOME application should associate itself at install-time with all the document types it can handle. Technical details on doing this can be found in the GnomeVFS API reference.

2.4. Using the Status Notification Area

Using the status notification area applications can notify the user of non-critical events (for example, arrival of new email, or a chat 'buddy' having logged on), and expose the status of active system processes (for example, a printing document, or a laptop's battery charging).

Following the guidelines in this section will help to clarify the difference in the user's mind between information presented in the notification area, and controls and information presented on other parts of the panel.

![[Warning]](images/warning.png) | Warning |

|---|

The utility of the notification area decreases rapidly when more than about four icons are always present. For this reason, icons that appear only temporarily in response to events are preferable. |

2.4.1. Notification Area or Panel Applet?

You should probably write an applet instead of using the notification area if:

clicking your notification area icon does anything other than opening a window directly associated with the icon (e.g. a mail folder window for a new mail icon, or a print queue window for printer notification icon), or

there are icon-specific options on its context menu for doing anything other than that

your application would ever need to display more than one notification icon at the same time

Guidelines

Use table perspective for icons representing physical devices, with the light source above and to the left of the represented object. For example, a printer icon during printing. See Section 9.1.1, “Perspective” for more about table perspective.

Use shelf perspective, with overhead lighting, for all other icons. For example, an envelope shown when new mail arrives. See Section 9.1.1, “Perspective” for more about shelf perspective.

For monitors or progress bars that change over

time, such as a battery charge monitor, clearly delimit the border of the area.

Guidelines

Only core GNOME programs may perpetually display an icon in the status area.

Non-core programs for which a perpetual icon may be useful must default to not perpetually showing the icon. Users may select to enable a perpetual icon for the application as a preference.

Guidelines

Icons should not usually appear animated. They may change to

indicate a change of state, but should not do so when that change

is occurs regularly rapidly. A battery status indicator would

usually change slowly, therefore an icon is appropriate. By contrast,

a load meter would always be changing, therefore it should use a flat

image.

Any icon may blink to indicate an error in deference to showing

an alert. For example, a printing-in-progress icon may blink when

there is a paper jam, but not when the printer is on fire - that

should show an alert.

Do not rely on blinking or animation as a means of alerting the user to any particular event.

Icons should respond to the these user actions.

(Keypresses apply only when the icon has focus, of course)

Guidelines

Double-click or Space key

should perform the icon's default action. Normally this should open a window with relevant data, for example:

the printer queue for a printing-in-progress icon.

the inbox for an incoming email iconi

the message for an incoming message

Right-click or Shift+F10

should present a menu for the icon containing at least

the icon's default action.

If the icon's properties may be altered, it should

have a menu item in its menu,

nd show its property panel in response to Alt+Enter.

Icons should obey normal tooltip conventions.

3.1. Parts of Windows and System Interaction

Give every window a title (with the exception of alerts and toolboxes). A good window title

contains information that is relevant to the user, and distinguishes a

particular window from other open windows. Omit information that does

not assist in this selection, for example the application's version

number or vendor name.

See the description of each particular window type for title

formats.

3.1.2. Borders and Window Commands

Most windows have borders, except certain shaped windows and some

torn-off windows. Do not attempt to draw your own window borders, but

instead provide hints to the window manager for the desired border type.

Different window commands are appropriate to different types of

window. See the description of each particular window type for a list of

appropriate window commands. These are the possible window commands:

-

Close.

Closes the window. Always draw this as

a button on the window border when relevant to the window type.

-

Maximize.

Causes the window to use all unused screen space.

-

Minimize.

Causes the window to be temporarily hidden. It will continue

to appear on the desktop window list.

-

Roll-up/Unroll.

Shows only the title bar of the window, as if it has been

"rolled up".

A non-modal window does not

restrict the user's interaction with other open windows on the

desktop in any way. Using non-modal windows gives the user maximum

flexibility to perform tasks within your application in any order and by

whichever means they choose.

An application modal window,

while it is open, prevents the user from interacting with other windows

in the same application.

A system modal window, while it

is open, prevents the user from interacting with any other window in any

application, including the desktop itself.

Guidelines

-

Use an application modal window only if allowing interaction

with other parts of the application while the window is open could

cause data loss or some other serious problem. Provide a clear way

of leaving the modal window, such as a Cancel

button in an alert.

-

Do not use system modal windows.

Focus is the means by which the user designates which window

should receive data from the keyboard, mouse or other input device. If

using a screen reader or similar assistive technology, focus may also

designate the window that the user wants to receive information about.

The focused window is considered the window the user is currently

"working with".

Ensure your application functions properly with the three

different mechanisms by which windows can receive focus in GNOME:

-

Click-to-focus.

A window is focused by clicking in it.

-

Point-to-focus.

A window is focused by moving the mouse pointer into it.

Sometimes known as "sloppy focus".

-

Keyboard focus.

A window is focused by using a keyboard shortcut such as

Alt+Tab.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Special restrictions for point to focus |

|---|

|

Note that point-to-focus places a number of restrictions on

GNOME applications that are not present in environments such as MacOS

or Windows. For example, utility windows shared between multiple

document windows, like the toolbox in the GIMP Image Editor, cannot be

context-sensitive— that is, they cannot initiate an action such as

Save on the current document. This is because

while moving the mouse from the current document to the utility

window, the user could inadvertantly pass the pointer over a different

document window, thus changing the focus and possibly saving the wrong

document.

|

3.1.5. Showing and Hiding Windows

How your application shows and hides windows can greatly affect the user's perception of your application, particularly its performance.

Guidelines

Always show a window as soon as possible, but make sure your window is the correct size before displaying it. Resizing a window after it is visible is disorienting and gives an unpolished look to your application.

If a window contains information that takes a few seconds to compute or display, it is often better not to fill it in completely before displaying the window. For example, a window containing a large text area can be shown

quickly, and then the text can be filled in afterwards (provided this does not result in the window resizing). This will make your application feel more responsive than if you had not shown the window until its content was complete.

Hide a window as soon as possible after it is

closed. Unless an alert might be shown, immediately hide a window that the user has closed by clicking the Close button in the window border--

your application can still perform any internal clean-up operations afterwards. Besides making the

system appear slow, not doing this can cause the window manager to think the application is not responding, and display an unnecessary alert to the user.

A primary window usually presents a view of the user's data,

such as a text document in a word processor application, an image in a

drawing program, or calculations in a calculator or spreadsheet

application. It may also be a view of something more abstract, like a

game. A single instance of an application may have more than one primary

window, and more than one kind of primary window.

A primary window is always shown on the panel window list.

A primary application window normally has a border, a menubar and a

statusbar, and may also contain one or more toolbars.

The most important element of a document-based application's

window title is the name of the open document. For other

applications, it usually the name of the application.

Guidelines

Use Filename

as the window title for document-based applications.

Do not use the full pathname, as

the filename alone is easier to distinguish amongst

other open window titles, for example on the window list.

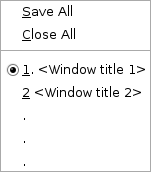

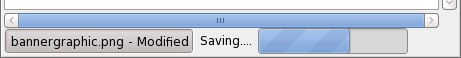

Example 3.1. Using document names as window titles

If the

pathname is important, for example the user has opened two documents

with the same name from different directories in the same application,

show the full pathname in the statusbar.

Before a new document has been saved for the first time, set

the window title to Unsaved <document type>.

For example,

Unsaved Drawing,

Unsaved Spreadsheet, or the more

generic Unsaved Document.

When a document has pending changes, insert an asterisk

(*) at the beginning of the window title.

For example, *Unsaved Drawing,

*AnnualReport.

For non-document-based applications, use

Application Name

as the window title.

Example 3.2. Using application names as window titles

Do not place version numbers, company names, or other information

that is of no immediate use to the user in the window title. These

consume space, making titles in limited spaces such as the system window

list less useful, and add more text the user has to scan to find useful

information. In a "beta" product, where version numbers are

critical for bug information, placing version numbers can be useful, but

remove them from stable releases. Place version information in the about

box instead.

While document names are most pertinent to users, we understand

that application developers may want to increase recognition of their

application. If you plan to include your application's name in the

title of a primary window, use the following format:

Document Name - Application Name.

This will ensure that the document name appears in limited space

situations such as the system window list.

![[Warning]](images/warning.png) | Warning |

|---|

Including the application name in the title of a document-based application is not recommended. |

![[Tip]](images/tip.png) | Tip |

|---|

Think about naming windows in the context of the panel window list. On a typical screen with a relatively small number of windows open, a window will have 20-30 characters of text and an icon. Consider which text will provide the most immediately obvious clues to a user looking for a particular window. |

Close, Maximize/Restore, Minimize, Roll-up/Unroll

3.2.3. Relation between Documents and Windows

3.2.3.1. Single Document Interface (SDI)

A single document interface places each document in its own

primary window. Toolboxes and other utility windows may be shared

between multiple SDI documents, but closing them should have no effect

on the document windows. Use SDI for your GNOME application unless

there is a compelling reason not to.

3.2.3.2. Multiple Document Interface (MDI)

A multiple document interface presents a paned, tabbed or

similar presentation of two documents

within a single window.

MDI has several inherent usability problems, so its use is

discouraged in applications. It is better to open each document in a

new primary window, with its own menubar, toolbars and statusbar, or

allow multiple instances of your application to be run simultaneously.

In either case, this leaves it for the window manager (acting on the

user's preferences) rather than your application to decide how to

group and present document windows from the same application.

3.2.3.3. Controlled Single Document Interface (CSDI)

In a typical SDI application, document windows are treated as

primary. For example, when all document windows have been closed, the

application (including utility windows) exits as well. In CSDI a utility

window is treated as the primary window. For example, closing this

utility window will close all document windows and exit the application.

![[Warning]](images/warning.png) | Warning |

|---|

Using CSDI is not recommended |

CSDI is sometimes used because document windows might be too

small to have menu bars. Typically this is not the normal use case for the

application, but does represent a significant minority use case. For

example, an image editor being used to edit small web page elements will

often result in very small document windows that cannot accomodate

a title bar.

A better way to address this problem is to allow menu bars to "collapse"

into an overflow button, in much the same way toolbars operate when the window

shrinks to below the toolbar width. This allows for small windows, but also

provides an opportunity for people to figure out where their menus have gone.

![[Tip]](images/tip.png) | Tip |

|---|

Note that if very small documents are the primary use

case for your application, you should consider finding a means to avoid windows

altogether. Windows are not an effective interface for dealing with large

numbers of small items. Consider looking for a fixed/automated layout system

for presenting the "documents". Also consider if the "documents" will be primarily

used in a higher level grouping, in which case that grouping could become the

document instead. |

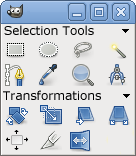

Utility windows, such as palettes and toolboxes, normally have

borders. They do not contain a menu bar, a toolbar, or a statusbar.

A utility window should not appear in the panel window list unless

it is, or may be, the only window shown by an application.

Otherwise, the utility window should be raised above the application when

the application window itself is selected from the window list.

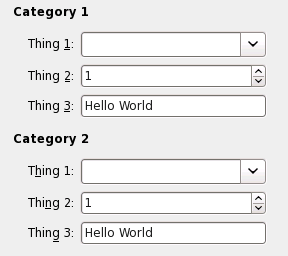

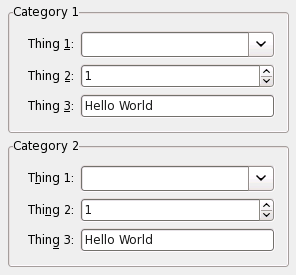

3.3.1. Instant apply windows

For windows that allow the user to change values or settings, such

as property and preference windows, update those values or settings

immediately to reflect the changes made in the window. This is known as

"instant apply". Do not make the user press an

OK or Apply button to make

the changes happen, unless either:

-

the change will take more than about one second to apply, in

which case applying the change immediately could make the system

feel slow or unresponsive, or

-

the changes in the window have to be applied simultaneously to

prevent the system entering a potentially unstable state. For

example, the hostname and proxy fields in a network properties

window.

If either these conditions affect only a few of the controls in

your window, arrange those controls together into one or more groups,

each with its own Apply button. Leave the rest of

the controls as instant apply.

Guidelines

Do not attempt to validate or apply changes caused by editing a

text field control until the user has moved focus to a different

control in the window, or the window is closed.

Validating after each keypress is usually

annoying and unnecessary. Exception: if the field accepts only a fixed

number of characters, such as a hexadecimal color code, validate and

apply the change as soon as that number of characters have been entered.

When the user moves focus to a different control, do not indicate an invalid entry by displaying an alert or undoing the change the user made. Both of these methods are particularly disruptive for focus-follows-mouse users, for whom focus may leave the control more often than it does for a click-to-focus user.

3.3.2. Explicit apply windows

If most of the controls in your window are not suitable for

instant apply, consider making the whole window "explicit

apply". An explicit apply window has these three buttons in its

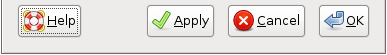

button box, plus an optional Help button:

-

Apply.

Applies all the settings in the window, but does not close

the window in case the user wishes to change their mind.

-

Cancel.

Resets all settings in the window to those that were in

force when the window was opened. Note: this must undo the effects

of all applications of the Apply since the

window was opened, not just the most recent one.

-

OK.

Applies all settings in the window, and closes the window.

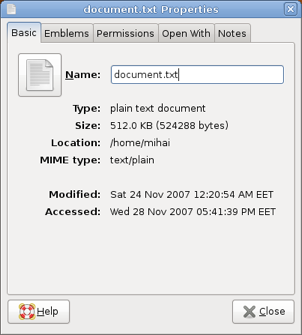

Property windows allow the user to view and change the

characteristics of an object such as a document, file, drawing, or

application launcher.

Title Format:

Object Name Properties

Window Commands:

Close, Minimize, Roll-up/Unroll

Buttons:

Place a Close button in the lower right

corner. A Help may be placed in the lower left

corner.

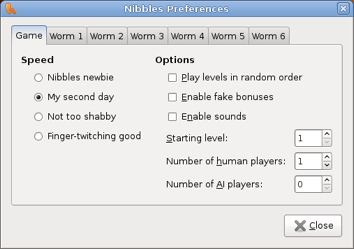

3.3.5. Preferences Windows

Preferences windows allow the user to change the way an

application looks or behaves.

Title Format:

Application Name Preferences

Window Commands:

Close, Minimize, Roll-up/Unroll

Buttons:

Place a Close button in the lower right

corner. A Help may be placed in the lower left

corner.

3.3.5.1. Customizing Fonts and Colors

If your preferences window allows the user to customize fonts or colors, use the following wording and layout as a guide for these controls:

Example 3.3. Recommended wording for overriding theme elements- replace with screenshot

(o) Use font from theme

(o) Use this font: [ Font selector ]

(o) Use colors from theme

(o) Use these colors:

Background: [ color selector ]

Foreground: [ color selector ]

The wording of the radio buttons may be more specific where required, for example, "Use monospace font from theme", or "Use background color from theme".

An alert provides information about the state of the application

system, or asks for essential information about how to proceed with a

particular task. It is distinct from other types of window in that it is

not directly requested by the user, and usually contains a message or a

question rather than editable controls. Since alerts are an unwelcome

intrusion into the user's work, do not use them except where necessary

to avoid potential data loss or other serious problems.

An alert has a border similar to that of a dialog, and is object modal.

An alert should not appear in the panel window list unless

it is, or may be, the only window shown by an application. For

example, an appointment reminder alert may be shown after

the main calendar application window has been closed.

Otherwise, an alert should be raised above the application when

the application window itself is selected from the window list.

Title Format.

Alert windows have no titles, as the title would usually

unnecessarily duplicate the alert's primary text. This way, users

can read and respond to alerts more quickly as there is less visual

noise and confounding text.

Resizing.

Alert windows are not resizable. If the user needs to resize your

alert, the text is probably not concise enough.

Window Commands:

None

![[Caution]](images/caution.png) | Alerts must stay above their parent |

|---|

|

Alerts do not appear in the system window list. Consequently, take

care to ensure that alerts stay above their parent window. Otherwise,

users will be likely to lose the alert and find your application

unresponsive for no apparent reason. Modal windows should always stay

above the window(s) they block.

|

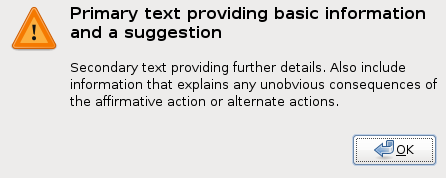

An alert may contain both primary and secondary text. The primary

text briefly summarizes the situation. The secondary text provides

additional information.

Make both the primary and secondary text selectable. This

makes it easy for the user to copy and paste the text to another

window, such as an email message.

Primary Text.

The primary text provides the user with a one sentence summary

of the information or suggested action. This summary should concisely

contain the essential details of the problem or suggestion. Every

alert has primary text, displayed in a bold font slightly larger than

the default. The primary text is punctuated in 'newspaper headline'

style, that is, it has no terminating period, but it may have a

terminating question mark.

Denote primary text with the pango markup:

<span weight="bold"

size="larger">Primary Text</span>

Secondary Text.

Secondary text provides a more in-depth description of the

problem and suggested action, including possible side effects.

Secondary text can also provide information that may be helpful in

allowing the user to make an informed decision. In most situations the

user should only need the primary text to make a quick decision, but

they may read the secondary text if they are unsure of the proper

course of action, or require extra details. Secondary text is

optional, but if used, place it one text line height beneath the

primary text using the default font size and weight.

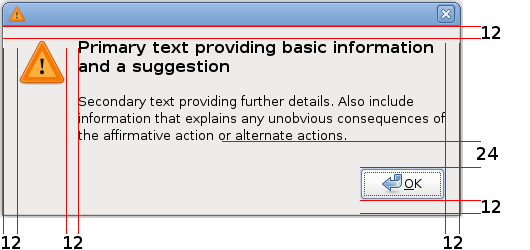

3.4.3. Spacing and Positioning Inside Alerts

Using clear, consistent spacing in alerts makes the message easier

to digest and the available responses more obvious.

Guidelines

-

The border around all edges of the alert, and the space

between the icon and the text, is 12 pixels.

-

The horizontal spacing between the buttons is 6 pixels.

-

Add one line break at the standard font size below both the

primary and secondary text, or 24 pixels if you are using Glade.

-

Align the top of the icon with the top of the primary text.

-

Left-align the message text, for western locales.

![[Tip]](images/tip.png) | Technical Details for Proper Layout |

|---|

|

Create a new GtkDialog window specifying the number of buttons

you wish the alert to contain (and a help button if appropriate). The

GtkDialog will contain a GtkVBox with an empty upper row, and a lower

row containing a GtkButtonBox with buttons in it. In the empty upper

row, place a new GtkHBox. In the left column of the GtkHBox place a

GtkImage. In the right column of the GtkHBox place a GtkLabel. Inside

the GtkLabel place Primary Text first

(using the appropriate Pango markup, see Section 3.4.1, “Alert Text”),

then put two linebreaks (return), then place

Secondary Text. Now change the properties

for each control according to these tables:

Table 3.1. Properties for the GtkDialog

| Property | Value |

|---|

| Title | (none) | | Border Width | 6 | | Type | Top Level | | Resizable | No | | Has Seperator | No |

Table 3.2. Properties for the GtkVBox (included in the dialog by

default)

Table 3.3. Properties for the GtkHBox

| Property | Value |

|---|

| Spacing | 12 | | Border Width | 6 |

Table 3.4. Properties for the GtkImage

| Property | Value |

|---|

| Y Align | 0.00 | | Icon Size | Dialog |

Table 3.5. Properties for the GtkLabel

| Property | Value |

|---|

| Use Markup | Yes | | Wrap Text | Yes | | Y Align | 0.00 |

|

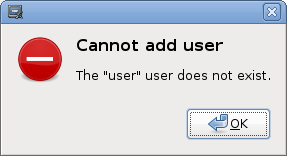

Display an error alert when a user-requested operation cannot be

sucessfully completed. Present errors caused by operations not requested

by the user by another means, unless the error could result in data loss

or other serious problems. For example, an error encountered during an

email check initiated by the user clicking a toolbar button should

present an error alert. However, an error encountered in an automated

periodic email check would more appropriately report failure with a

statusbar message.

An error alert...

-

uses the stock error icon.

-

presents a selectable message and an OK

button. The button is placed in the bottom-right corner of the

alert. Pressing Enter may dismiss the error alert.

-

may present a convenience button to allow immediate handling

of the error. For example, a Format... button

in a "This disk is not formatted" alert. Place this button

to the left of the affirmative button.

Window Commands:

Roll-up/Unroll

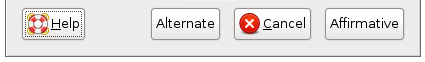

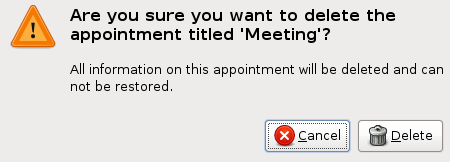

3.4.6. Confirmation Alerts

Present a confirmation alert when the user's command may

destroy their data, create a security risk, or take more than 30 seconds

of user effort to recover from if it was selected in error.

A confirmation alert...

-

uses the stock warning icon.

-

presents a selectable message and a button labelled with

a verb or verb phrase

describing the action to be confirmed, or labelled

OK if such a phrase would be longer than three

words. This button is placed in the bottom right corner of the

alert.

-

presents a Cancel button that will

prevent execution of the user's command. This button is placed

to the immediate left of the OK or equivalent

button.

-

may present an alternate action button or a convenience

button. Place this button to the left of the Cancel

button.

Window Commands:

Roll-up/Unroll

3.4.6.1. Save Confirmation Alerts

Save confirmation alerts help ensure that users do not lose

document changes when they close applications. This makes closing

applications a less dangerous operation.

Primary Text.

Save changes to document Document Name

before closing?

You may replace “document” with a more appropriate

description, for example “image” or “diagram”

if the document in question is not primarily text.

Secondary Text.

If you close without saving, changes from the last

Time Period will be discarded

The secondary text provides the user with

some context about the number of changes that might be unsaved.

Buttons.

Close without Saving,

Cancel, Save

When a confirmation alert is needed,

present it immediately. If the user confirms closing without saving,

hide the alert and the document or application window immediately,

before doing any necessary internal clean-up.

If the user chooses to save before

closing, hide the alert immediately but show the document window until the document is

saved, in case an error occurs. Then hide the document window immediately after it has been saved successfuly.

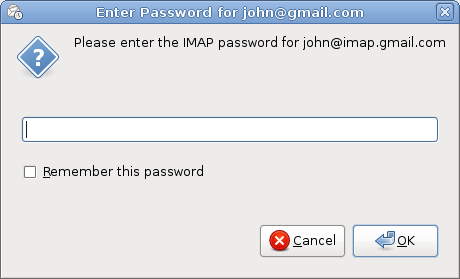

3.4.7. Authentication Alerts

Authentication alerts prompt the user for information necessary to

gain access to protected resources, such as their username or password.

Authentication alerts are a special kind of alert because they are both

routine and largely unavoidable. Every attempt should be made to retain

information entered into an authentication alert as long as is possible

within security constraints.

Guidelines

Use the

stock authentication icon.

Show

a labelled field for each required item of information. Suggested fields

are Username and Password (in

that order) where appropriate.

If it is

secure to retain the username longer than the password, pre-fill the

username field and give focus to the password field when the alert is

displayed.

Show a button labelled with

a verb or verb phrase describing the authentication action, or

OK if there is no appropriate phrase or such a

phrase would be longer than three words. Place this button in the bottom

right corner of the alert.

Do not

enable the OK or equivalent button until all

fields that require input have been attended to by the user. Remember

that not all fields may require input however, for example an empty

password may be acceptable in some applications.

Show

a Cancel button that will prevent authentication

and close the alert. Place this button to the immediate left of the

OK or equivalent button.

Place

any alternative action or convenience button to the left of the

Cancel button.

When

the user presses Return in the last field, activate the

default button. When the user presses Return in any

other field, move focus to the next field.

Window Commands:

Roll-up/Unroll

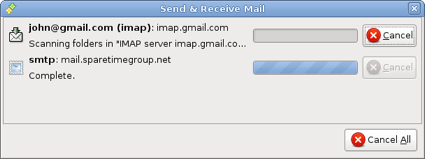

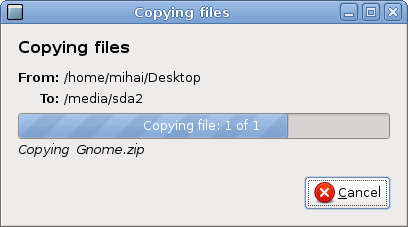

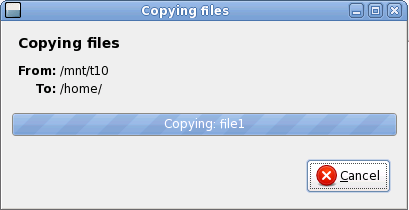

A progress window can be used to provide feedback

during an operation that takes more than a few seconds. See Section 6.17, “Progress Bars” for more details about proper use of

progress bars.

A progress window should always appear as an independent window in a window list.

If progress of a task makes a window temporarily unusable, do not present a modal dialog-like progress window in front of it.

Instead, present progress somewhere in the original window, making all its other elements temporarily insensitive.

This helps reduce visual clutter.

Title Format.

Progress windows should have a title representing the overall

operation: for example Copying Files, Installing, or Calling.

As with other window titles, do not end progress window titles with an ellipsis.

Resizing.

Progress windows should be resizable if they contain non-static

information the user may want to copy (for example, the source URL in a

download progress window). Otherwise they should not be resizable.

Guidelines

-

It is often better to use the progress bar contained in many

primary windows' statusbar rather than a progress window. See

Section 7.4.2.1.1, “Progress Windows vs. the Statusbar” for details on

choosing between the two.

-

Progress windows should use primary and secondary text like an

alert. See Section 3.4.1, “Alert Text”

-

The progress bar text should provide an idea of how much work

has been completed. It is better to provide specific information

rather than a unitless percentage. For example, "13 of 19 images

rotated" or "12.1 of 30 MB downloaded" rather than

"13% complete".

-

If possible, an estimate of the time left until the operation is

complete should also be included in the progress bar text. Indicate

that the "time left" is an estimate using the word

"about".

-

Immediately beneath the progress bar, place italicized text

indicating the current sub-operation being performed. This might be a

step in a sequence, "Contacting control tower for permission to

land", or it could be the current object being operated on in a

bulk operation, "Rotating MonaLisa.png", "Rotating

StarryNight.png".

-

If the operation in progress is potentially hazardous

(destructive, costly, etc) or heavily taxes a limited resource for

more than ten seconds (network bandwidth, hard disk, CPU, etc),

consider placing a Pause toggle button to the right of

the Cancel button. When paused, the italicized

current sub-operation text should have " (Paused)" appended.

This will allow users to perform important tasks requiring that

resource, or give them time to think whether they want to procede with

a dangerous operation they inadvertantly triggered.

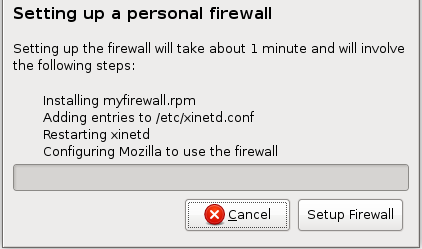

Occasionally a procedure is comprised of a series of user

performable actions. In these cases, particularly when it is desirable

that the user acquire some familiarity with the actions involved in a

procedure, checklist windows may be used.

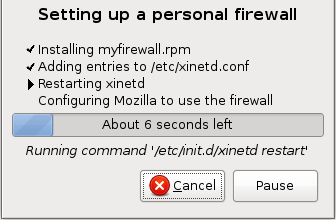

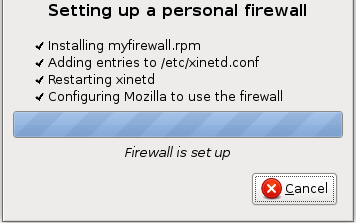

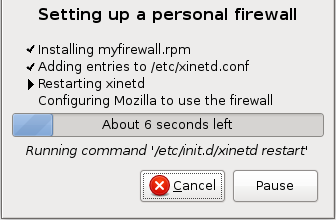

Example 3.4. Firewall Setup Wizard

A personal firewall setup wizard might install the firewall

package, add entries for the firewall to /etc/xinetd.conf, restart the

internet super-daemon, and configure the user's web browser to

operate through the firewall. It may be desirable that the user is

exposed the series of actions involved in setting up the firewall to

increase the chances that they will be sucessful in making

modifications later, if they so desire.

Guidelines

-

If knowing the series of steps in an operation isn't that

useful to the user, just use a regular progress window. Remember

that you are probably more interested in the information than most

users, many of whom will find the technical steps confusing rather

than helpful.

-

Unlike regular progress windows, checklist windows should not

close automatically when the operation is complete and should

require explicit user input before they begin. This is because one

of their purposes is to inform the user concerning an

operation's contingent steps.

-

The progress bar indicates progress in the overall operation,

not each step. While this is more difficult to program, it is the

information most useful to the user. Just estimate how long each of

the steps takes relative to each other and assign each step a fixed

ratio of the progress bar's progress accordingly.

-

Do not use a checklist window for a

series of internal programmatic steps, use a regular progress

window. For example "Connect to mail server",

"Authenticate with mail server", "Download

messages", "Disconnect" would not

be an appropriate series of steps for a checklist window, but would

be appropriate sub-operation steps for a regular progress window.

A dialog provides an exchange of information, or dialog, between the

user and the application. Use a dialog to obtain additional information

from the user that is needed to carry out a particular command or task.

A dialog should not appear in the panel window list.

Any open dialogs should be raised above the application when

the application window itself is selected from the window list.

Title Format:

Name of command that opened the dialog

(without any trailing ellipsis)

Window Commands:

Minimize, Roll-up/Unroll

Buttons:

Follow the guidelines for Alert buttons, see Section 3.4.2, “Alert Buttons”.

Your dialog may specify a default button, that is activated when the

user presses the Return key. See Section 3.3.3, “Default Buttons” for guidance on choosing an appropriate

default button.

A clean, logical dialog layout helps the user to quickly

understand what information is required from them.

Guidelines

Arrange controls in your dialog in the direction that people read.

In western locales, this is generally left-to-right, top-to-bottom.

Position the main controls with which the user will interact as close to

the upper left corner as possible. Follow similar guidelines for

arranging controls within groups in the dialog, and for specifying the

order in which controls are traversed using the Tab

key.

When opening a dialog, provide initial keyboard focus to the

component that you expect users to operate first. This focus is

especially important for users who must use a keyboard to navigate your

application.

Provide and show sensible default values for as many of the

controls in your dialog as possible when it is opened, so the user does

not have to generate the information from scratch. These defaults may

come from system settings (for example, hostname or IP address), or from

information that the user has previously entered in this or another

application (for example, email address or network proxy).

See Chapter 8, Visual Design for more detailed information on

arranging controls in dialogs.

See Section 6.16, “Tabbed Notebooks” for information on using

tabbed notebook controls in dialogs.

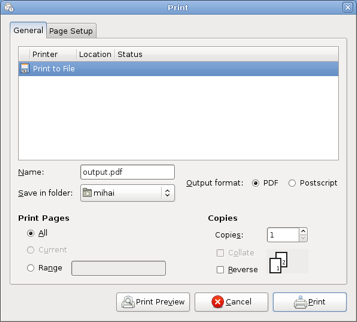

The gtk and GNOME libraries provide standard dialogs for many

common tasks, including opening and saving files, choosing fonts and

colors, and printing. Always use these when the user is performing one

of these tasks. You may modify the dialogs to reflect the needs of your

particular application (for example, adding preview

Play and Stop buttons to

the Open File dialog in an audio application), but do not change or

remove features so much as to make them unrecognizable.

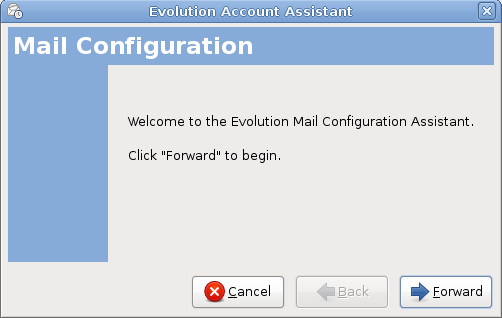

An assistant is a secondary window that guides the user through an

operation by breaking it into sequential steps. Assistants are useful for

making complex operations less intimidating, as they restrict the

information visible to the user at any given moment.

Because assistants provide a relatively small number of controls on

the screen at any given time, they have sufficient space for inline

documentation. Therefore, do not include a Help

button in an assistant window. If you cannot make an operation

sufficiently clear in an assistant without resorting to a

Help button, you need to simplify it further.

Assistants do have major downsides. After using an assistant

it is often hard to figure out where the individual settings aggregated

into the assistant are stored. Often people will resort to re-running

the assistant, re-entering many settings that they don't want to change.

![[Warning]](images/warning.png) | Warning |

|---|

Assistants are often used in situations where a better

solution would be to simplify, or even better automate, the process.

Before using an assistant to step people through a complex operation,

consider if the operation can be fundamentally simplified so an

assistant is unnecessary. |

Window Commands:

Close, Minimize/Unminimize, Roll-up/Unroll

The first page provides the user with the "big picture".

Place the title of the assistant in the window's title bar and the

assistant's title area, along with an optional picture. Beneath

this, state the goal of the assistant, and, if it is not obvious, where

the user can find the information the assistant will be asking for.

Title Format:

Assistant Title

Buttons:

Cancel, Forward

Content pages contain the actual settings of the assistant.

Summarize the type of setting present on each content page in its title

area. For example, Mail Server.

Title Format:

Assistant Title - (Current

Page of Total Pages)

Buttons:

Cancel, Back,

Forward

The last page should summarize the settings that will be changed

by the assistant, and how the user can modify them later.

Title Format:

Finish Assistant Title

Buttons:

Cancel, Back,

Finish

6.1. Using Controls Effectively

GNOME provides a set of controls, also known as widgets, which allow

users to interact with your applications. Using these controls

appropriately and not altering their standard behavior is important. This

allows users to predict the effects of their actions, and thus learn to

use your application more quickly and efficiently. Controls that behave in

non-standard ways break the user's mental model of how your

application works, and dilute the meaning of the interface's visual

language.

Although they are known as "widgets" in the GNOME APIs and

developer documentation, do not use this term in your user interface or

user documentation. Refer to them by their specific names (for example,

"buttons" or "menus"), or by the generic name

"controls".

Sometimes it does not make sense to allow the user to interact with

a control in the current context, for example, to press a

Paste button when the clipboard is empty. At these

times, make the control insensitive

to minimize the risk of user error. While a control is insensitive, it

will appear dimmed and will not be able to receive the focus, although

assistive technologies like screenreaders will still be able to detect and

report it.

It is usually better to make a control insensitive than to hide it

altogether. This way, the user can learn about functionality they may be

able to use later, even if it is not available right now.

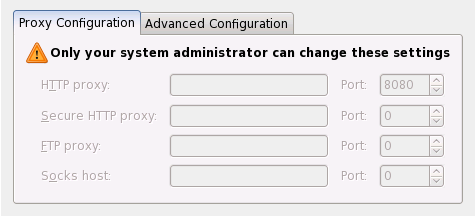

In a network-managed environment, like a computer lab, system

administrators usually want to "lock down" the values of certain

settings, or remove them from the user interface altogether. This makes

it easier for them to troubleshoot any problems that their users may

encounter. In GNOME, the correct way for the system administrator to do

this is by restricting write access to the GConf keys corresponding to

those settings.

When you are designing your application, consider which settings a

system administrator might want to make unavailable to users. These may

typically include:

-

Settings that, if set wrongly, could prevent the application

from functioning at all. For example, proxy settings in a network

application.

-

Settings that could refer to networked resources. For example,

the Templates directory in an office application, where shared

stationery such as fax cover sheets might be stored.

-

Settings that customize the user interface, other than those

required for accessibility. For example, certain menu, keyboard or

toolbar customization options.

Your application needs to decide every time these controls are

displayed whether or not they are available for editing, depending on

the writeable state of the GConf key that holds its value. In the

simplest case, your code for each control could look like that in the

example below.

Example 6.1. Sample code fragment showing how to make a GConf-locked control

insensitive

if (!gconf_key_is_writable (http_proxy))

gtk_widget_set_sensitive (http_proxy_field, FALSE);

Include a section for system administrators in your user guide,

explaining which settings they can lock, and their corresponding GConf

keys.

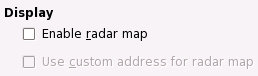

Explain to the user why these controls cannot be edited at this

time. You can do this with static text, tooltips or online help,

depending on the situation. For example:

Note that although they cannot be edited, the settings are still

visible and selectable, and may be copied to the clipboard.

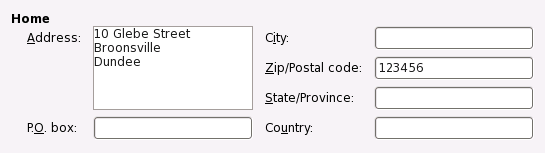

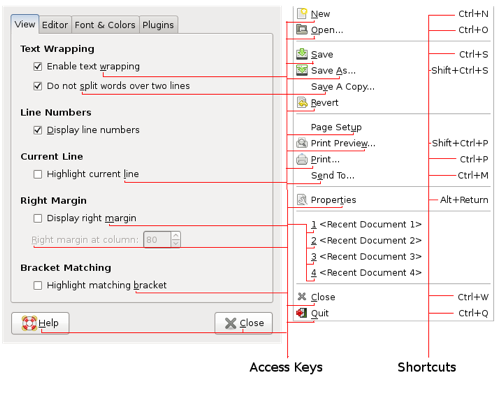

Text entry fields are used for entering one or more lines of plain

text. In GTK 2, the GtkEntry

control is used for single-line text entry, and GtkTextView

for multiple-line text entry.

Guidelines

-

Label the entry field with a text label above it or to its left,

using sentence capitalization.

Provide an access key in the label that allows the user to give focus

directly to the entry field.

-

Right-justify the contents of entry fields that are used only

for numeric entry, unless the convention in the user's locale

demands otherwise. This is useful in windows where the user might want

to compare two numerical values in the same column of controls. In

this case, ensure the right edges of the relevant controls are also

aligned.

-

When the user gives focus to an entry field using the keyboard,

place the text cursor at the end of the existing text and highlight

its contents (but don't overwrite the existing PRIMARY clipboard

selection). This makes it

easy to immediately overtype or append new text, the two most common

operations performed on entry fields.

-

Size text entry fields according to the likely size of the

input. This gives a useful visual cue to the amount of input expected,

and breaks up the dialog making it easier to scan. Don't make all

the fields in the dialog the same width just to make everything line

up nicely.

-

In an instant-apply property or

preference window, validate the contents of the entry field

when it loses focus or when the window is closed, not after each keypress.

Exception: if the field accepts only a fixed

number of characters, such as a hexadecimal color code, validate and

apply the change as soon as that number of characters have been entered.

-

Provide a static text prompt for text boxes that require input

in a particular format or in a particular unit of measurement. For

example:

-

Where possible, provide an additional or alternative control

that limits the required input to the valid range. For example,

provide a spinbox or slider if the required input is one

of a fixed range of integers, or provide access to a GtkCalendar

control if the user has to enter a valid date:

This is less error-prone than expecting the user to format their

text input in some arbitrary format. You may still want to provide the

entry field control as well, however, for expert users who are

familiar with the required format.

-

If you implement an entry field that accepts only keystrokes

valid in the task context, such as digits, play the system warning

beep when the user tries to type an invalid character. If the user

types three invalid characters in a row, display an alert that explains the valid inputs

for that textfield.

-

The cursor blink rate is globally defined by the XSettings

"gtk-cursor-blink" and "gtk-cursor-blink-time".

Standard toolkit controls use these and they must

not be altered in applications by any means. New controls with text

cursors must respect these global values.

6.4.1. Behavior of Return key

Normally, pressing Return in a dialog should

activate the dialog's default button, unless the focused control

uses Return for its own purposes. You should therefore

set the activates-default

property of most entry fields to TRUE. (Note that GtkTextView does not

have such a setting— pressing Return always inserts a

new line.).

However, if your dialog contains several entry fields that are

usually filled out in order, for example Name,

Address and Telephone Number,

consider setting the activates-default property on

those entry fields to FALSE. Pressing Return should

then move focus on to the next control instead.

Doing this will help prevent the user from accidentally closing the

window before they have entered all the information they wanted to.

As a further safeguard, remember not to set the default button in

a dialog until the minimum amount of required information has been

entered, for example, both a username and a password in a login dialog.

Again, in this case you should move focus to the next control when the

user presses Return, rather than just ignoring the

keypress.

If you need to provide a keyboard shortcut that activates the

default button while a GtkTextView control has focus, use

Ctrl+Return.

![[Note]](images/note.png) | Note |

|---|

|

Gtk does not currently move focus to the next control when

Return is pressed and either activates-default=FALSE,

or there is no default button in the window. For now,

Return does nothing in these situations, so remember

to implement the focus change behavior yourself.

|

6.4.2. Behavior of Tab key

Normally, pressing Tab in a single-line entry

field should move focus to the next control, and in a multi-line entry

field it should insert a tab character. Pressing Ctrl+Tab

in a multi-line entry field should move focus to the next control.

If you need to provide a keyboard shortcut that inserts a tab

character into a single line entry field, use Ctrl+Tab.

You are unlikely to find many situations where this is useful, however.

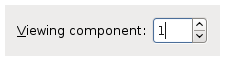

A spin box is a text box that accepts a range of values. It

incorporates two arrow buttons that allow the user to increase or decrease

the current value by a fixed amount.

Guidelines

-

Use spin boxes for numerical input only. Use a list or option

menu when you need the user to select from fixed data sets of other

types.

-

Use a spin box if the numerical value is meaningful or useful

for the user to know, and the valid input range is unlimited or fixed

at one end only. For example, a control for specifying the number of

iterations of some action, or a timeout value. If the range is fixed

at both ends, or the numerical values are arbitrary (for example, a

volume control), use a slider control instead.

-

Label the spin box with a text label above it or to its left,

using sentence capitalization.

Provide an access key in the label that allows the user to give focus

directly to the spin box.

-

Right-justify the contents of spin boxes, unless the convention

in the user's locale demands otherwise. This is useful in windows

where the user might want to compare two numerical values in the same

column of controls. In this case, ensure the right edges of the

relevant controls are also aligned.

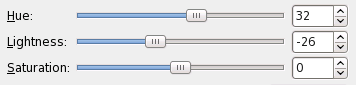

A slider allows the user to quickly select a value from a fixed,

ordered range, or to increase or decrease the current value. The control

looks like the type of slider that you might find on an audio mixing desk

or a hi-fi's graphic equalizer. In gtk, you implement a slider using

the GtkHScale or GtkVScale controls, for horizontal or vertical sliders

respectively.

Guidelines

-

Use a slider when:

-

adjusting the value relative to its current value is more

important than choosing an absolute value. For example, a volume

control: the average user will usually think about turning the

volume up or down to make a sound louder or quieter, rather than

setting the peak output to a specific decibel value.

-

it is useful for the user to control the rate of change of

the value in real time. For example, to monitor the effects of a

color change in a live preview window as they drag the RGB

sliders.

-

Label the slider with a text label above it or to its left,

using sentence capitalization.

Provide an access key in the label that allows the user to give focus

directly to the slider.

-

Mark significant values along the length of the slider with text

or tick marks. For example the left, right and center points on an

audio balance control in Figure 6.7, “A simple slider control”.

-

For large ranges of integers (more than about 20), and for

ranges of floating point numbers, consider providing a text box or

spin box that is linked to the slider's value. This allows the

user to quickly set or fine-tune the setting more easily than they

could with the slider control alone.

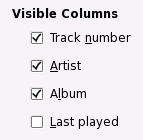

Check boxes are used to show or change a setting. Its two states,

set and unset, are shown by the presence or absence of a checkmark in the

labelled box.

Guidelines

-

Do not initiate an action when the user clicks a check box.

However, if used in an instant-apply property

or preference window, update the setting represented by the

check box immediately.

-

Clicking a check box should not affect the values of any other

controls. It may sensitize, insensitize, hide or show other controls,

however.

-

If toggling a check box affects the sensitivity of other

controls, place the check box immediately above or to the left of the

controls that it affects. This helps to indicate that the controls are

dependent on the state of the check box.

-

Use sentence

capitalization for check box labels, for example

Use custom font.

-

Label check boxes to clearly indicate the effects of both their

checked and unchecked states, for example, Show icons in

menus. Where this proves difficult, consider using two

radio buttons instead so both states can be given labels. For example:

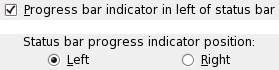

The single check box in this example is ambiguous, as it is not

clear where the "progress indicator" will go if the box is

unchecked. Two radio buttons are better in this case, as they make the

options clear.

-

Provide an access key in all check box labels that allows the

user to set or unset the check box directly from the keyboard.

-

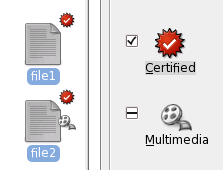

If the check box represents a setting in a multiple selection

that is set for some objects in the selection and unset for others,

show the check box in its mixed state. For example:

In this example, both selected files are hidden (since their

filenames start with "."), and the emblems on their icons show

that neither file is writeable, but one is readable. The

Readable check box is therefore shown in its

mixed state. .

When a check box is in its mixed state:

-

clicking the box once should check the box, applying that

setting (when confirmed) to all the selected objects

-

clicking the box a second time should uncheck the box,

removing that setting (when confirmed) to all the selected objects

-

clicking the box a third time should return the box to its

mixed state, restoring each selected object's original value

for that setting (when confirmed)

-

Label a group of check boxes with a descriptive heading above or

to the left of the group.

-

Use a frame around the group if necessary, but remember that

blank space often works just as well and results in a less

visually-cluttered dialog.

-

Do not place more than about eight check boxes under the same

group heading. If you need more than eight, try to use blank space,

heading labels or frames to divide them into smaller groups.

Otherwise, consider using a check box list instead— but you probably

also need to think about how to simplify your user interface.

-

Try to align groups of check boxes vertically rather than

horizontally, as this makes them easier to scan visually. Use

horizontal or rectangular alignments only if they greatly improve the

layout of the window.

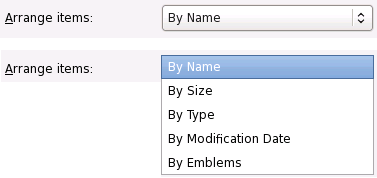

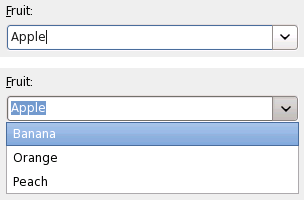

6.12. Drop-down Combination Boxes

Drop-down combination boxes combine a text entry field and a dropdown list of

pre-defined values. Selecting one of the pre-defined values sets the entry

field to that value.

Guidelines

-

Only use a drop-down combination box instead of a list, drop-down list or radio

button group when it is important that the user be able to enter a new

value that is not already amongst the list of pre-defined choices.

-

Do not initiate an action when the user selects an item from the

list in a drop-down combination box. If used in an instant-apply property or preference window, update

the setting represented by the drop-down combination box immediately if possible. If

this isn't possible due to the contents of the entry field being

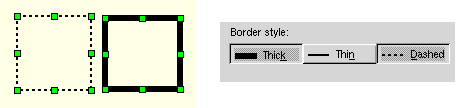

invalid while the user is still typing into it, update the related

setting when the drop-down combination box loses focus instead.

-

If the user types a value into the drop-down combination box that is not already

in the drop-down list, add it to the list when the drop-down combination box loses

focus so they can select it next time.

-

Interpret user input into a drop-down combination box in a case-insensitive way.

For example, if the user types blue,

Blue and BLUE into the

same drop-down combination box on different occasions, only store one of these in the

combo's dropdown list, unless your application makes a distinction

between the different forms (which is usually a bad idea).

-

Label the drop-down combination box with a text label above it or to its left,

using sentence capitalization.

Provide an access key in the label that allows the user to give focus

directly to the drop-down combination box.

-

Use sentence

capitalization for the dropdown list items, for example

Switched movement.

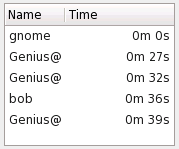

A list control allows the user to inspect, manipulate or select from

a list of items. Lists may have one or more columns, and contain text,

graphics, simple controls, or a combination of all three.

Guidelines

-

Always give list controls a label, positioned above or to the

left of the list, in sentence

capitalization. Provide an access key in the label that allows

the user to give focus directly to the list.

-

Make the list control large enough that it can show at least

four items at a time without scrolling. For lists of ten or more

items, increase this minimum size as appropriate.

-

If the list appears in a dialog or utility window, consider

making the window and the list within it resizable so that the user

can choose how many list items are visible at a time without

scrolling. Each time the user opens this dialog, set its dimensions to

those that the user last resized it to.

-

Do not use lists with less than about five items, unless the

number of items may increase over time. Use check boxes, radio buttons or an drop-down list if there are fewer

items.

-

Only use column headers when:

-

the list has more than one column, or

-

the list has only one column, but the user may wish to

re-order the list. (This is rarely useful with single column

lists).

In most other situations, column headers take up unnecessary

space, and the extra label adds visual clutter.

-

Always label column headers when used. If the column is too

narrow for a sensible label, provide a tooltip for the column instead.

Apart from its obvious use, this will help ensure that assistive

technologies can describe the use of the column to visually impaired

users.

-

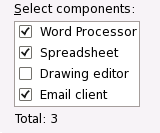

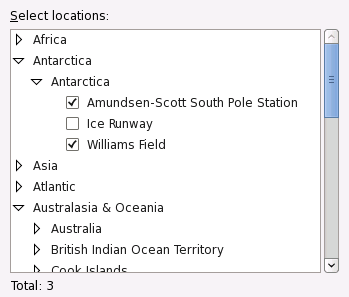

Consider using a check box list for multiple-selection lists, as

these make it more obvious that multiple selection is possible:

If you do this, you should normally set the list control itself

to be single-selection, but this depends on the particular task for

which it will be used.

-

For multiple selection lists, show the number of items currently

selected in a static text label below the list, for example,

Names selected: 3. Such a label also makes it

more obvious that multiple selection is possible.

-

Consider providing Select All and

Deselect All buttons beside multiple selection

lists, if appropriate.

Users often prefer to sort long lists, either alphabetically or

numerically, to make it easier to find items. Allow users

to sort long or multi-column lists by clicking on the column

header they want to sort.

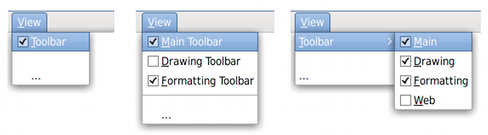

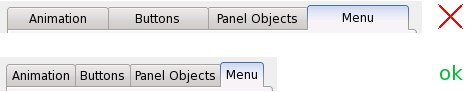

Guidelines